Activist Maria Teresa Griffin, who proved her mettle in fight against East L.A. prison, dies

It can be difficult to locate Maria Teresa Griffin’s name in historical archives or newspaper clippings documenting revitalization or social justice efforts throughout Los Angeles’ Eastside.

Yet her handiwork is everywhere.

Griffin worked for 49 years at Barrio Planners Inc., an architectural firm in East L.A. that blends urban planning with activism. She served as a receptionist, architectural aid and accountant.

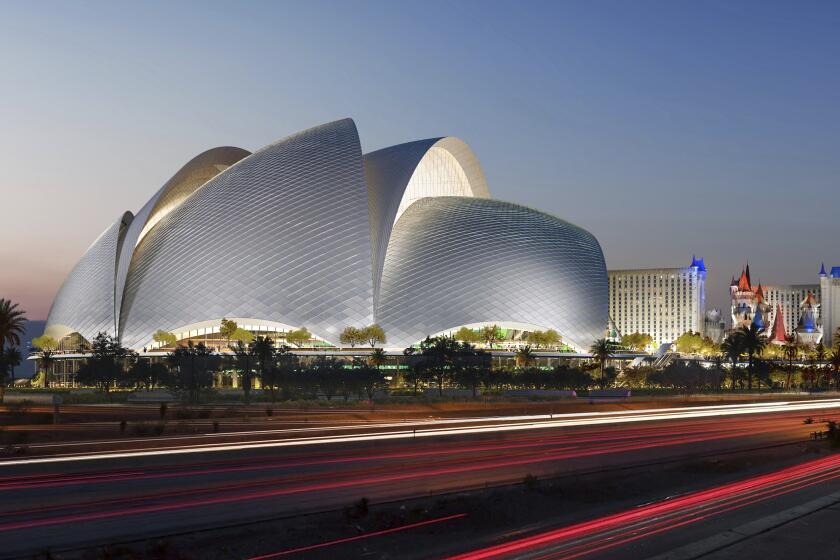

Barrio Planners helped renovate downtrodden Whittier Boulevard in part by designing East L.A.’s now-famed 65-foot steel archway in 1986. The firm, led by chief architect and founder Frank Villalobos, also designed Lincoln Heights’ El Parque de Mexico and Boyle Heights’ Mariachi Plaza, and it renovated parts of Olvera Street.

One of Griffin’s greatest accomplishments, however, concerns a facility never built.

When California Gov. George Deukmejian advocated for a prison in East L.A. in the mid-1980s, Villalobos, Msgr. John Moretta of Boyle Heights’ Resurrection Church and Lincoln Heights community activist Steve Kasten rallied coalitions to derail the project.

They relied on Griffin, who utilized her thick Rolodexes and neighborhood connections to buttonhole politicians, community members and others to fight.

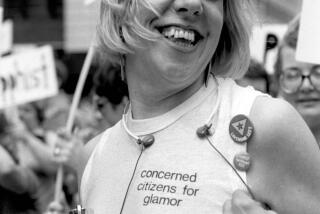

Griffin eventually became a founding member and longtime treasurer of the group that symbolized Eastside resistance to the prison — the Mothers of East Los Angeles.

The association, numbering about 100 members in the mid-1980s, began a battle against the prison project that lasted for six years, holding numerous rallies in L.A. and Sacramento until, in 1992, the plan was nixed.

The Mothers continue to fight environmental injustices, but without this trailblazer.

Griffin died Jan. 15 at 74. She had been suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, according to her sister, Olivia Haddock.

Haddock, one of Griffin’s younger sisters, said Griffin never married or had kids but spent her days surrounded by her eight siblings’ combined 64 children and grandchildren.

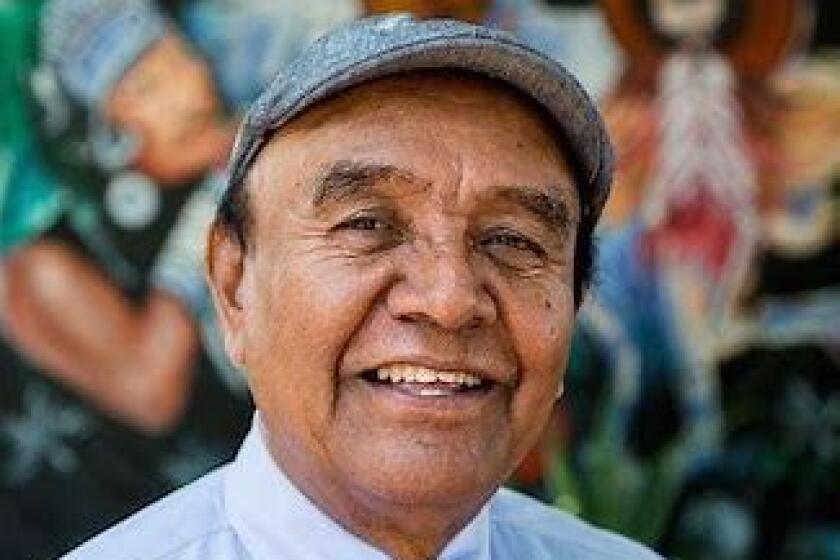

Arturo Ybarra, who founded the Watts Century Latino Organization and pushed for unity among Black and Latino people in South Los Angeles, has died. He was 79.

Griffin had a comfortable, middle-class upbringing, Haddock said. The family was staunchly Roman Catholic and lived in Commerce and, later, Monterey Park. Griffin’s father, Edgar G. Griffin, born in Mexico to an Irish family, was a 101st Airborne paratrooper who survived the Normandy landing on D-day and was awarded a Purple Heart. Mary Dominguez Griffin, her mother, was a longtime See’s Candies employee.

Maria Teresa Griffin’s career took flight on Halloween 1974, when the 25-year-old walked into Barrio Planners’ office looking for a job.

The only available position was for a secretary who could type 82 words a minute.

“She sat down on one of our IBM typewriters and she just flew,” Villalobos said. “She only made one error on our test — one error. She got hired on the spot.”

Griffin eventually moved from secretary to landscaping architect assistant after taking drafting classes at East Los Angeles College.

She was a quick learner, according to Villalobos, who said Griffin easily transitioned to computers when Barrio Planners bought its first model in 1982. She eventually helped train some of the architects on Microsoft Excel and AutoCAD, 2-D and 3-D drafting and design software.

But her true passion was numbers, according to Villalobos. She returned to ELAC, this time enrolling in accounting classes.

Upon graduating, she became the firm’s accountant, eschewing a backroom office to remain near the entrance and customers.

There, Griffin struck up a friendship with rising Eastside politician Gloria Molina, who often stopped by to chat when she was working for then-Assemblymember Art Torres.

The church doors opened, and people streamed into the foyer. They grabbed a purple-lined program detailing many of Molina’s accomplishments. Assemblymember. Councilmember. Supervisor.

Molina was one of the first and most vocal advocates against the plan — endorsed by Deukmejian as well as The Times — to install a 1,750-bed prison adjacent to Boyle Heights, and would often speak about thwarting its construction.

Molina, Griffin and Villalobos made up three parts of a potent resistance movement that drafted Moretta, Kasten and others into the fight.

Griffin, known as Terry, “was this bridge between the very grassroots campaign that included area residents and advocacy groups with the more business folks like the Chamber of Commerce and small businesses opposed to the prison,” Moretta said. “Terry knew everybody.”

For the anti-prison campaign, Griffin tapped the more than 2,000 names and numbers she had compiled through her work with Barrio Planners.

She and other Mothers members often trekked on a weekly basis to protests in Sacramento and around Los Angeles.

When Gov. Pete Wilson signed legislation killing the prison proposal in 1992, Villalobos said, “it was an amazing victory for the Eastside, for the Mothers and for Terry.”

After serving in the California Assembly, Montañez used her connections and iron will to bring hundreds of millions of dollars to the San Fernando Valley and other underserved communities to clean up polluted areas and beautify neighborhoods.

Griffin continued on as treasurer with the Mothers for decades. She stepped away from many activities two years ago when she was diagnosed with ALS.

Though ill, Griffin traveled to Maui for the wedding of her niece, Jenika McMurray, Haddock’s youngest daughter, in September 2022.

Griffin had told McMurray and Haddock that her attendance was unlikely.

“And then one day I saw that she bought an airline ticket,” Haddock said. “She loved her family, and she was a fighter. That’s her legacy.”

Griffin is survived by sisters Haddock, Ana Padilla, Gloria Brady, Irene Gaffney, Carolyn Velasco and Diana O’Connor and brother Edward Griffin.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.