It was a particularly chaotic time. As the war in the Middle East raged on, sparking relentless and horrific news headlines, a family member unexpectedly landed in the hospital here in California. Visits to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, doomscrolling and sleepless nights left me drained.

Perhaps that’s why an invitation to Forest Therapy — something I might have previously dismissed as silly — piqued my curiosity. I’d have tried anything to slow the incessant whirl of concerns in my head.

So on a recent Saturday, I found myself laying in a cool, dewy patch of grass, early in the morning, in a lush palm grove at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. The San Marino gardens weren’t yet open to the public and the grounds were eerily quiet but for the whooshing of leaves in the wind and the intermittent trilling of wild parrots.

The two-part class ($60 for members, $80 otherwise) — led by forest therapy guide Debra Wilbur over consecutive Saturdays — promises to help participants “discover pathways to restore emotional and physical well-being” during a guided nature immersion.

I was skeptical, but game. Seeking refuge in nature is hardly new and need not be exclusive — why pay for it? And how was this therapy?

Turns out, Forest Therapy is a revamping of Forest Bathing, which became especially popular in the early days of the pandemic, when people sought refuge outdoors. The practice — immersing oneself in nature, while utilizing all the senses, to promote mindfulness and reap calming benefits — grew out of the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, which was popularized in Japan in the ’80s. Shinrin-yoku literally translates to “forest bathing” — but that presented a branding problem when the practice picked up steam, decades later, in the U.S., Wilbur explains. “People had concerns: ‘do I need to wear a bathing suit in the woods?’” she says. So the term Forest Therapy is now more commonly used, though the trained practitioner is considered more of a guide and the forest, the actual therapist.

Visitors to the Huntington Library can tour a restored 18th century Shoya House, a residence from rural Japan.

Wilbur’s particular spin on the practice is heavily focused on “therapeutic circle sharing,” in which participants reflect, in groups, as they go along. “It’s intimate. It’s powerful. You’ll see,” she says, promising an experience that’s both communal and individualistic.

About 18 of us show up for Wilbur’s class that Saturday for different reasons, but we’re all seeking the same thing: to get out of our heads and into the moment. To feel grounded and to slow down.

Wilbur — who looks every bit the quintessential earth mother, with her salt-and-pepper hair pinned into a messy bun and wearing an aqua cape, cactus-print socks and hiking boots — gives a short talk about the origins of forest bathing. Then she has us relax in the grass for a 30-minute, guided body scan meditation. Her voice is soft and soothing: “Just imagine that anything that’s clinging to you is falling off,” she coos. We close our eyes, or stare up at the blur of drifting clouds against the pale morning sky.

Sound baths are everywhere in Los Angeles, even in churches. Here’s what it’s like to experience the singing bowls and gongs in grand, acoustic settings.

Afterward, Wilbur leads us on a series of walking “invitationals,” calling upon our senses to help us more deeply connect with the natural environment. At each new location, in a different part of the Huntington’s gardens, she asks us to move slowly and intentionally — “wander directionless” — while focusing on her newest sensory request.

In the Palm Garden, we’re asked to open our mouths and taste the air on different parts of our tongue; in the Subtropical Garden, we’re asked to fondle the plants, to run our hands gently over their prickly spines or silky smooth leaves; at the Lily Ponds, filled with koi, ducks, turtles and a large snapping turtle, we’re invited to close our eyes and tune into the water’s ecosystem. Wilbur gives a talk about the globally circulating nature of water “running underground and coming up and through us, sustaining us, flowing through the trees, their roots and leaves, evaporating into the sky and raining back down again, back through us.”

“Conceivably,” she says, “the tears we shed today may, a year from now, be part of a waterfall somewhere else. Water has a voice, a messaging system, that’s the invitation, to engage in that.”

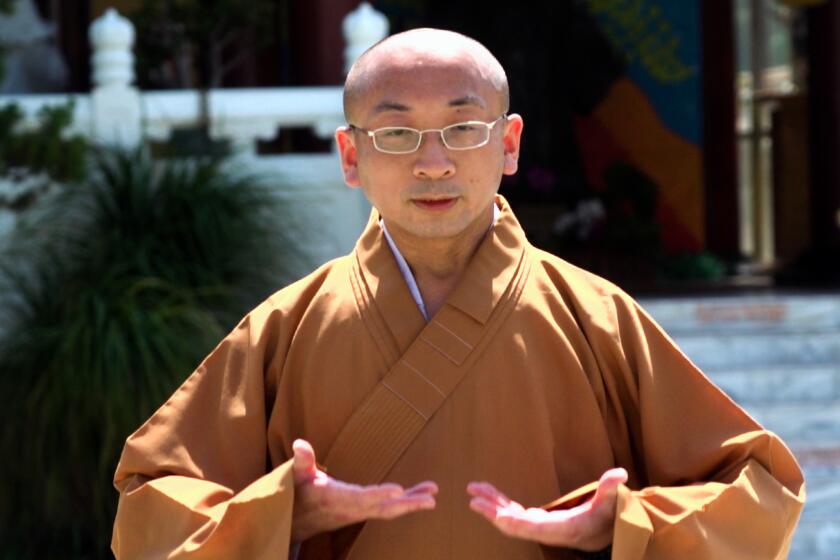

Wilbur led a 30-minute body scan meditation, to ground participants in the moment. (Yuri Hasegawa / For The Times)

A Forest Therapy participant meditates against a large tree in the Huntington’s cypress grove. (Yuri Hasegawa / For The Times)

Between locations, we’re reminded to walk at a snail’s pace, to feel the ground beneath our feet, the uneven surfaces and varying textures, spongy and responsive one minute, rock hard the next.

After each invitational, Wilbur gathers us back together with a shrieking bird call.

“Kuh-Kaw! Kuh-Kaw!,” she wails, neck craned backward and cupping her mouth.

Lotions, potions, edibles, visuals, toys and games to help turn the hamster-wheel run of life into a walk in the park. And these items are great gifts for the holidays.

We again form a circle to share our reflections. (Yes, snark creeps in: “Hello, my name is Deb and I’m a whirlwind-aholic looking to slow down,” I joke to myself, before it’s my turn. But the collective earnestness is contagious.)

“It gave us the permission to feel and to be present and to stop,” says one participant.

“It was affirming, grounding,” adds another.

“I noticed the geometry of the ferns adjacent to the chaotic vines,” notes another.

The Huntington began expanding its wellness offerings in 2021. Wilbur’s class is part of its “Restore + Explore” series, which also includes twice-monthly tai chi classes. The program is an outgrowth of the pandemic, says public programs and community engagement coordinator Joy Yamahata. When nearly every cultural institution in Southern California was shuttered, the Huntington’s gardens, which reopened as of July 2020, provided a therapeutic escape.

“People were scared, uneasy, things were shut down. So this was a response — to use the gardens as a sanctuary for safety and peace,” Yamahata says. “So we wanted to expand wellness in the garden.”

Wilbur, a visual artist and former art director for TV and films, was trained at the Prescott, Ariz.-based Assn. of Nature & Forest Therapy, which offers training internationally. She’s since led hundreds of sessions, over the last seven years, in various settings — forests, but also the beach, in canyons and public gardens. She especially enjoys leading full moon sessions (“it’s like sharing secrets in the dark”) and sessions at proper institutions, such as the Huntington, before they are open to the public. It feels a little like “breaking the rules,” she says, not unlike “Night at the Museum,” where you’re encouraged to run free and touch the surroundings.

“Coming into formal gardens, people treat them very formally and carefully — as well they should, not doing damage,” Wilbur says. “But the invitation to step off the trail, to engage with plants by touching them, by smelling them, tasting the air — it sort of loosens people’s ideas of what’s possible when they come into a more staid setting.”

At the end of our two-hour session, Wilbur gathers us in a dense and shady cypress grove, under a particularly unwieldy cedar tree, a snaggle of thick, twisty branches draping along the ground. She offers us freshly brewed tea made of lavender and a mixture of rose petals and rosehips. Then we each get a piece of black tourmaline, considered a so-called “grounding stone” that is said to offer protection.

“It’s all a reminder to take the time to slow down and log into your senses,” Wilbur says, before offering us bubble wands and a lesson on steadying the breath to calm the central nervous system.

“Start to visualize letting stressors go — pop! — or send out beautiful wishes or intentions into the world,” she says.

So we do.

As the grove fills with glistening bubbles popping in the trees, we enjoy one final circle share — and then we mingle. It’s a tea party in the forest.

“It’s easy to get all caught up in the news, in the fear, in what’s happening in our own lives,” says Shannon Leavitt, 60, a first time Forest Therapy participant. “Just the habit of having to do, and go fast, and get stuff done — it’s a hamster wheel and it’s really nice to be reminded to step off and just be.”

Meditation is not just about sitting still. Monks from Hacienda Heights’ Hsi Lai Temple show us different ways to maintain a meditative state while carrying on everyday activities.

Rhonda Waller, a 47-year-old psychotherapist from Eagle Rock who specializes in trauma, grief and loss, says the last several months, with the writers’ and actors’ strikes compounded by the war in the Middle East, has been especially rough for her clients. She recently discovered Forest Therapy — today is her second class — and she plans to bring her team of therapists to Wilbur’s next class so they can explore the practice as a healing modality.

“I want them to have the grounding experience and to know this is a resource to be able to guide people, or themselves, for self-care,” she says. “It’s a recalibration. It’s not just the lived experience, but hearing other people’s experiences that helps.”

Forest Therapy is hardly an antidote to world peace nor a cure-all for personal problems. But guided meditation in nature, supported by talk therapy, focused my attention, provided connection and calm.

It was an escape of sorts — a salve after which everything felt brighter and more fragrant — if just for a fleeting few hours.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.